When I first started lifting weights, I used to try my best to push myself until I couldn’t do any more reps. I didn’t know any better because nobody told me otherwise. And when I looked at how Arnold Schwarzenegger trained and the bodybuilding culture, it seemed like going to complete failure was the ultimate goal.

For a long time, I thought that in order for a workout to be successful, I had to reach the point where my muscles couldn’t move anymore, even if it meant needing someone to help me with the weights to avoid getting crushed (yes, that actually happened).

But what if I told you that the key isn’t to push your muscles to the point of complete failure?

Whether your goal is to gain muscle mass, improve specific muscle groups, or simply enhance your overall health through resistance training, the idea of seeking failure is often misunderstood and misapplied. It’s a major reason why many people don’t achieve amazing results from their workouts. There’s a significant difference between breaking down your muscles to promote growth and completely demolishing them to the extent that recovery becomes more difficult.

Muscle growth is indeed connected to muscle fatigue. However, if you want to develop stronger muscle fibers or increase muscle mass, pushing yourself to failure should be done sparingly. In fact, in most cases, the best approach for both short-term and long-term growth is to find a way to challenge yourself by adding more repetitions, sets, and weights without reaching the point where your muscles give up. (And this is separate from the risk of injuries, which are much more likely when training to failure.)

To help you understand how hard to push yourself and determine the appropriate intensity for your workouts, we sought advice from Jordan Syatt, the owner of Syatt Fitness. In this post, he provides five questions that you should consider in order to develop a more effective approach to your workouts.

So Should I Train To Failure?

By Jordan Syatt

Think back to when you first started lifting weights. Remember how you approached your workouts? You probably grabbed the heaviest dumbbell you could handle and did as many reps as you could until you couldn’t move the weight anymore. Then you rested and repeated the process. It was simple, but sometimes simplicity can be a good thing.

However, this simplicity is also why many people feel frustrated with their gym workouts. They’re not sure how hard to push themselves on each set. They may not know the best way to build muscle or strength. They simply follow the exercises listed in their training program.

But here’s the thing: The results you see from your gym sessions depend on various factors, including muscular tension, metabolic stress, and muscular damage. Manipulating these variables can be done in different ways, and many people assume that pushing every set to the point of muscle fatigue and discomfort is the key. This is why the concept of “training to failure” is heavily debated in the fitness industry, and honestly, it’s often misunderstood.

After studying this topic extensively, I’ve come to realize that there’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Some people believe that taking every set to failure is the secret to success, while others argue that it’s a recipe for injuries and overtraining. The truth is, the answer depends on the individual and their specific needs, goals, and preferences. If you’re committed to your training sessions, it’s essential to personalize your workouts as much as possible. Before pushing yourself to muscle failure on every set, there are some important factors to consider.

So, let’s take a moment to think about these factors before deciding whether training to failure is right for you.

Question 1: Is Training to Failure a Must?

Unfortunately, there isn’t a wealth of research on training to failure. However, for physique competitors and strength athletes looking to improve performance, increasing muscle hypertrophy is often crucial. Training to failure might activate a greater number of motor units and potentially enhance muscle growth, making it a suitable approach for these individuals.

Willardson et al. conducted a comprehensive review of the available literature on failure-based training. Based on their analysis, they concluded that training to failure is a valid method for promoting muscle hypertrophy, facilitating maximum strength gains, and overcoming plateaus.

However, it’s important to consider Willardson’s cautionary statement that “training to failure should not be performed repeatedly over extended periods due to the risk of overtraining and overuse injuries.” Therefore, the lifter’s training status and goals should guide the decision-making process regarding training to failure.

In another study, it was found that training to failure resulted in a significantly higher secretion of growth hormone compared to non-failure-based training. Although this finding doesn’t prove that training to failure is superior to other methods, it may support the success that many athletes, bodybuilders, and fitness enthusiasts have experienced with failure-based training.

Your goals and training style will have the most significant influence on whether and when you should push your body to failure.

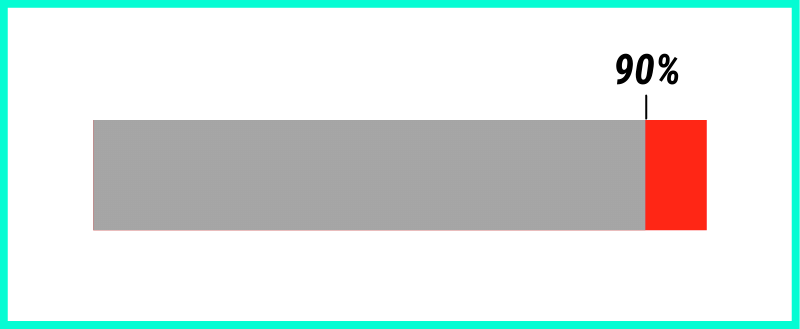

Question 2: Are You Exceeding the 90-Percent Max Rule?

When it comes to training to failure, the intensity of your workouts plays a vital role in determining their effectiveness and suitability. Training intensity refers to the percentage of weight you lift compared to your one-repetition maximum (1-RM). In my opinion, it’s best to avoid training to failure when working with weights at or above 90 percent of your 1-RM.

Training to failure with such heavy weights won’t significantly contribute to muscle growth and may even hinder your strength gains. If you do reach the point of absolute or complete failure, it’s not advisable to do so with the maximum amount of weight you can handle in exercises like pushing, pressing, deadlifting, or squatting.

Additionally, training to failure with weights close to your maximum will likely lead to compromised technique, increasing the risk of injury. Remember, weightlifting is an activity for a lifetime, but it’s important to be mindful of the risks involved.

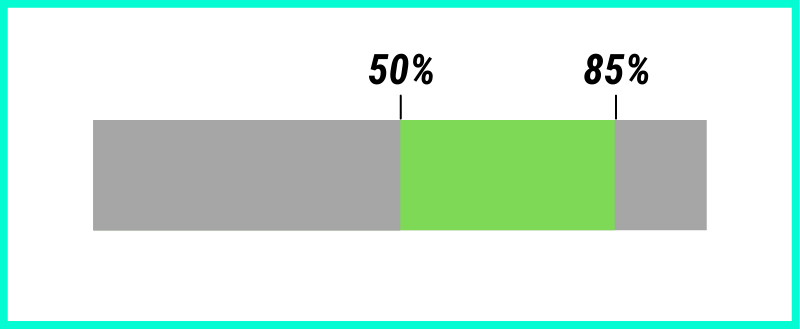

Generally, training to failure is more suitable for training intensities ranging from 50 percent to 85 percent of your 1-RM.

However, I rarely recommend training to failure at either end of this range. These percentages serve as helpful guidelines for most intermediate and advanced trainees. Keep in mind that training to failure at 50 percent of your 1-RM can be time-consuming and may not be ideal for those with limited time for their workouts. On the other hand, working with 85 percent of your 1-RM still involves heavy weights, so having a spotter is strongly encouraged.

Question 3: How Often Should You Train to Failure? (Take Your Training Age into Account)

There are three main stages or levels in the trainee continuum: beginner, intermediate, and advanced.

Your current training status determines what your body needs, and the methods of training may vary significantly depending on whether you’re a beginner, intermediate, or advanced trainee.

For instance, beginner trainees should primarily focus on developing proper form and technique in compound movements like squats, bench presses, deadlifts, and chin-ups. Pushing beginners to absolute failure would likely do more harm than good because maintaining proper form becomes increasingly challenging when fatigued. In other words, if you’re a beginner and haven’t consistently trained for at least two years, it’s generally best to avoid training to muscle failure, even when working below 90 percent of your 1-RM.

Instead, you can try using the “reps in reserve” (RIR) method. This approach works well for beginners and is also highly effective for advanced lifters. Rather than pushing to complete failure, aim to reach a different level of fatigue. Set a target rep range, such as eight reps, and make sure you have two reps in reserve (2 RIR). This allows you to work at an intensity level that challenges your muscles while deliberately leaving a few reps “in the tank.” Determining the exact number of reps you have in reserve may require some trial and error. However, once you figure it out, this approach is an excellent way to increase reps, weights, and sets while focusing on form, fatigue, and recovery.

If you’re not a beginner, intermediate and advanced trainees can train to failure more frequently. Following the 90-percent rule and staying within the 60 to 85 percent range of your 1-RM, you can train to failure two to four times per week.

The frequency at which you should push yourself will depend on your goals and the specific exercises you perform.

Question 4: What Is Your Goal and Mindset?

Your desired goal plays a significant role in shaping your training program, including whether or not training to muscular failure is appropriate for you.

Let’s consider the differences between powerlifters and bodybuilders as an example. Powerlifters focus on maximizing their strength, including training their nervous system to handle heavy weights. As a result, they train at relatively high intensities of their 1-repetition maximum (1-RM). Powerlifters also prioritize full-body, compound movements that require a high level of skill to maintain proper form.

On the other hand, bodybuilders aim for muscle growth and tend to train at comparatively lower intensities of their 1-RM. They understand that strength alone is not the sole factor for achieving their goals. Bodybuilders often emphasize smaller, isolation movements targeting specific muscle groups, which require less skill to maintain proper technique.

Due to these varying approaches and exercise choices, bodybuilders can train to failure more frequently than powerlifters.

It’s worth noting that many elite powerlifters do incorporate training to failure into their routines. As a world record powerlifter myself, I regularly include failure-based training in my programs. However, I tend to avoid training to failure in big, compound movements and primarily focus on intensities ranging from 60 to 80 percent of my 1-RM.

Ultimately, your goal will guide the decision of whether training to failure aligns with your needs, preferences, and objectives.

Question 5: What Exercises Are You Performing?

The complexity and skill required for a particular exercise play a significant role in determining how frequently it should be trained to failure. Generally, exercises that demand a higher level of skill should be performed to failure less often, whereas exercises that are less skill-intensive can be more acceptable for training to failure.

Let’s take snatches as an example. Snatches are considered one of the most complex lifts, and training them to failure can be risky. On the other hand, simpler multi-joint movements like variations of the chin-up, bench press, and lunge are suitable for failure-based training, but they should be approached with extreme caution. The same goes for exercises such as squats.

Lastly, single-joint exercises like bicep curls, triceps extensions, and calf raises involve less complexity in their movement patterns. These exercises are more appropriate for training to failure and can be incorporated with less concern.

The Bottom Line

The idea of training to failure, pushing your muscles to the point where they can no longer perform any more reps, is often misunderstood and misapplied. Many people believe that reaching complete failure is necessary for a successful workout, but this may not be the case.

While muscle growth is connected to muscle fatigue, it’s important to find a balance between breaking down your muscles to promote growth and completely overexerting them, which can hinder recovery. Training to failure should be done sparingly, especially with heavy weights, as it can compromise technique and increase the risk of injury.

Your specific goals, whether they’re centered around strength or muscle growth, and the complexity of the exercises you perform will influence whether training to failure is suitable for you. It’s important to personalize your workouts and consider these factors before deciding on the appropriate intensity for each set.